20.6.2022

THE IMMORTALITY GAMEPLAN

An essay on early cinematic fame

If you ever wondered how a mere mortal is transformed into a deity, then I’d like to direct you to chapter three of Garbo, a Biography, published in 1995 and written by the American film historian Barry Paris. It’s a bridging chapter, a brief explanation of the time between Greta Garbo’s first sizeable film appearance – as the young duchess Elizabeth in The Saga of Gösta Berling – and her arrival in Hollywood at the request of Louis B. Mayer. It covers one year – 1924 – and the making of one film – The Joyless Street (Die freudlose Gasse, 1925). But everything you need to know is there: the mechanics of star-making, the negotiations and the manoeuvring, the opportunism and the manipulation. Being fed into this machine is an attractive young woman with potential but next to no say-so about her career. What is happening to her has happened to other famous film actors. In her case, the process will end in myth.

The star is an imaginary construct. She lives in our minds as an ageless phantom. We can’t form images of her mundane domestic existence and don’t really want to. Beauty gives her a free pass to another plane. But beauty in cinematic terms is tied up in all kinds of presentational imperatives. How a person is photographed, the words that come out of her mouth, the face opposite hers, the dress, the physique, the types of roles. And of course, the youth. It’s a concoction. A banal one in practice and utterly reliant on us mortals as willing collaborators.

So, who are the players in this revealing story? Firstly, a 19-year-old Swedish girl called Greta Gustafson, from a poor background and with an adolescent crush on the theatre. Then there’s Mauritz Stiller, 40 years old, “loud, egotistical and imperious”, a film director and pioneer of Swedish cinema. And finally, G. W. Pabst, an Austrian director who will go on to great things working with some of the most interesting female stars of the late twenties and early thirties.

In the preceding year, the girl – who had been accepted into the Royal Dramatic Theatre Academy in Stockholm – landed herself a supporting part in a historical screen drama called The Saga of Gösta Berling – in Paris’s words, a “kind of Swedish Elmer Gantry”. Gustafson, now Garbo, stood out in her role. There was definitely something about her, a presence, promise; and the director, Stiller, was in the prefect position to make something of it. He was very persuasive and, for a young woman in Garbo’s position, impossible to contradict. Just a few months after signing her contract with the theatre academy, she resigned and became Stiller’s personal student. She was in awe of Stiller and was now his pet project. So much of this story is about chance. The lucky break of Gösta Berling, the timings, the locations. But so much more is about intention and clever positioning. Stiller’s aim, suggests Paris, was to create the Dream Woman and Garbo presented him not only with the raw materials, but her full acquiescence.

Stiller was hatching all kinds of deals in Sweden and abroad but none of them was succeeding and eventually he took Garbo and her Gösta Berling co-star, Einar Hanson, to Berlin – the hotspot of ground-breaking European filmmaking. “The Garbo flower was about to blossom in the miraculously creative soil of 1925 German film,” writes Paris. But it wasn’t solely Stiller who was behind this flowering. Pabst’s role was at least as pivotal. The Austrian director and producer was not a well-known figure at the time, still building his name, but already with an interest in creating films of emotional power and honesty. He’s now known for discovering and promoting the work of exceptional actresses, most notably Louise Brooks, and for bringing a psychological realism to Weimar Cinema. Pabst was casting for Die freudlose Gasse, an adaptation of a novel which had been very successfully serialised in an Austrian newspaper. Its writer, Hugo Bettauer, set his story in a single Viennese street, the backdrop to a complex web of lives and stories, bound together by a moment of financial crisis. Pabst was not employed by a major studio and so had full artistic control of his work, but his casting decisions had to be financially canny. As Sarah F. Hall points out in her study of the making of The Joyless Street, small production companies could only expect loans from German banks if they guaranteed that their films would get substantial national and international attention. Casting, therefore, was a crucial strategic factor. Pabst managed to bring on board two huge names in European film: the powerfully charismatic Danish leading lady of film, Asta Nielsen, and none other than Dr Caligari himself, Werner Krauss (who plays the truly hideous butcher). Pabst had seen Garbo in Gösta Berling and insisted that he wanted her for the role of the dutiful daughter, Greta Rumfort. He was something of a lone voice in his conviction that she was right for the part, with even his film editor Marc Sorkin dismissing her as a “nothing – just a good-looking girl.”

Greta Rumfort is the daughter of a widowed civil servant, who gambles his pension on shares which then lose their value. The gentle, stoical young woman must pick up the pieces, while keeping her head morally above water. In contrast Maria – Asta’s Nielsen’s character – takes a run at her misfortune but ends up getting entangled in a murder. Both women are doing what they can to cope with poverty. As Sara F. Hall points out, while the female characters are substantially outnumbered by males, they nonetheless hold the narrative interest of the film. The men, she says, “shape the social and material circumstances in this fictional version of post-war Vienna, but it is the women who must navigate the fallout”. In this joyless street women resort to using their sexuality as their only currency. Greta is increasingly pulled in this direction only to be saved at the last minute.

Knocked about by fortune, the role required someone who could do haunted and on-the-back-foot. It would come to mean a lot of lingering close-ups and emoting of submerged distress and anxiety. And it’s at this point that you could argue the first stage of the deification process begins. Pabst knew he had the perfect Greta Rumfort in Garbo, sure he could translate that naturally doleful expression into the very real-feeling inner struggles of a vulnerable young woman . But Stiller was in control of his protegee’s career and it wasn’t a case of simply handing her over. A future star needed a star’s wages. He told Pabst that Garbo wouldn’t be interested in appearing in the film unless she was paid the same as Asta Nielsen, a veteran movie actor by then, having appeared in around 60 films.

Stiller didn’t stop there. He wanted his own cinematographer, Julius Jaenzon, to film Garbo. If ever there was a clue as to his motives in creating something mythical out of his young disciple, then surely this was it. Wrangling over film photography was central to the negotiations because these early depictions of Garbo would set a standard image. How that face was captured and presented was a form of branding. By using his own photographer, Stiller could keep control of the brand, could continue to mould and perfect that face.

Pabst had given in on the money but put up a fight over the photographer, having already hired the highly-regarded Guido Seeber. Both men were pioneers in their field but no director will give up his cinematographer lightly and Pabst stood firm. And it wasn’t only a question of angles and lighting for Stiller. He argued that Garbo’s face needed the best film stock. It had to be Kodak and not Agfa, he said. But Kodak was expensive and hard to come by and Pabst had to send to Paris for it at great expense. Even with the finest film stock and with Seeber behind the camera, Pabst still had to work on getting Garbo’s face just right and hired a specialist called Oertl to devise her optimum light mix.

How did the 19-year-old novice respond to all this attention being lavished on her? She was a bag of nerves. Very early on it became evident that when the camera was trained solely on her face, she was trembling with fear. But Pabst came up with a solution that didn’t involve on-set counselling. Having already played around with film speeds for effect elsewhere in the script, he now applied the same principal to her close ups, speeding up from the usual 18 frames per second to 25 frames per second. The result was a blurring of the nervous tic and – by chance – a more ethereal feel to every frame in which she appeared. The technique, writes Sarah F. Hall, “provides a softness and emphasis on Garbo’s eyes and hands that would have been passed over at a regular shooting speed.”

Eyes and hands were soon to be associated with Garbo, part of her allure and her exceptionality. Could the emphasis have been born at this moment and as a cover for her inexperience? Hall states that the softening, slow-motion technique was carried over from Pabst’s movie into her earliest Hollywood film outings.

Stiller had interfered with several aspects of the filming of The Joyless Street, changing parts of the script and even coming up with one of its central motifs – the fur coat which Greta is persuaded to purchase by the wily boutique owner, played by Valeska Gert. Eventually, his carping got him banned from the set. Garbo had enjoyed working with Pabst (the high regard was mutual) and considered staying in Berlin, but Stiller had other ideas and knocked her down to size. She was to stay with him, he insisted, and that would mean leaving Europe and heading to Hollywood. If she was his meal ticket, then it wouldn’t last long. Her ascendancy at MGM was meteoric, whereas his directing career never fully took off in the States and he returned to Sweden in 1927, dying a year later.

The Joyless Street was a big hit in Europe, especially in France, but proved too controversial for British and American censors, where it was either cut to pieces or banned outright. It set Pabst up for a serious career as a depicter of female psychologies, with the outstanding Pandora’s Box (Die Büchse der Pandora, 1929) and Diary of a Lost Girl (Tagebuch einer Verlorenen, 1929) still ahead of him. Barry Paris ties the film’s success in with Garbo’s presence as much as Pabst’s vision.

“Much of the credit went to the Swedish girl who now, to many, was Pabst’s discovery as much as Stiller’s… Garbo’s acting had a restraint that was startling at the time, as fragile as her personality – even if it was largely the result of stage fright. That ripening style would become familiar later in her Hollywood films. And her director here was an important factor in nurturing it.”

Significantly, Pabst was a gentle director, coaxing the best out of his actors – as opposed to the tyrannical Stiller. Paris believes that this father-figure role so early in her career had a lasting influence. “Re-evaluated in terms of her subsequent evolution,” he writes, “Pabst’s influence on Garbo’s acting was far more profound and lasting that Stiller’s.”

But it takes more than decent acting skills to enter the cinematic pantheon and Stiller was well aware of what she needed to rise above the rest. He taught Garbo to be special. He advised her to stay mysterious, to let the public guess at who she was, to give very little of herself away. And – who knows? – maybe he’s the one who warned her right from the start that, if she wanted to protect her legacy, she’d have to get out of the business while still young. Because that’s exactly what she did 15 years and 26 films later at the age of 36.

*

I’ve been thinking about stardom in early cinema history. Its genesis as a concept, the process of it and its psychological impact (on the human being it transforms into a deity as well as the other humans who willingly buy into it). We construct these gods out of the sum of their roles and it’s almost impossible to let go of our perceptions. (How often has the media of late referred to Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow during his libel trial with Amber Heard?)

In the very earliest days of moving pictures, before it could be called cinema and was more a fairground side-show, the actors were of no account, certainly no more prominent than the director and camera operator, usually less so. As movies became longer and more sophisticated, audiences wanted to know the names of the personalities with whom they were so intimately engaging and to see them again and again. With names, the faces became more memorable. With names, the actors became more valuable.

It was a new kind of fame. It travelled instantly, crossed the globe as fast as a reel of film could. The gods and goddesses remained as they were captured on screen, barely ageing. They existed to be looked at. And we would pay money to look at them. The creation of stars went hand in hand with a new revenue stream. Our gods have a worth. Or their commercial worth makes them into gods. When Mauritz Stiller forged his Dream Woman, he gave her a monetary value and negotiated over her. To keep her value, she had to continue being who and what she was: beautiful, slim, foreign, ageless, mysterious. Garbo and other stars were very aware of their worth and what they had to do to maintain it. When Charlie Chaplin – film’s first stratospheric star – got wind of how popular he was and what the audiences liked about him, he asked his boss, Mack Sennet, to increase his pay to an unheard of $1,000 a week. Sennet said no and the young actor – only 25 at the time – went to Essanay, where his potential value could be further expanded.

The gods of early cinema may seem ethereal but were surely weighed down by having to keep up their end of the bargain. Psychologists have explored the impact of fame on an artist’s mental state and found it, on the whole, damaging. Or rather, damaging if you’re already predisposed to levels of insecurity. The self-consciousness hypothesis in relation to celebrities suggests that being watched and scrutinised by the wider world leads the subject to a miserable degree of self-scrutiny. “Fame may ultimately make some people vulnerable to certain forms of self-abuse, in part because it leads to higher levels of self-consciousness,” writes Mark Schaller, of the University of British Columbia. The psychobiographer, William Todd Schultz, argues that while artists want and seek fame, many of them are “simply temperamentally unsuited to be famous”. He suggests that in some cases it might be due to a social background that hasn’t prepared them for the world they are entering.

Garbo – like Chaplin, Cary Grant and many others – came from poverty and obscurity, before being catapulted into a place of public adulation. Having to hide social insecurities – not to mention sexual ones – must bring with it unbearable stress. In addition to concealing who you are, you might have to look on quietly as your life is represented as something quite different to reality. According to the Barry Paris biography, Garbo’s legendary love affair with the silent screen actor, John Gilbert, was more an obsession on his part and a useful tolerance on hers. But, from MGM’s point of view, the public’s speculation as to the couple’s love life could only have been a good thing when it came to publicising their erotic encounters on screen.

Did they know it was happening? Did Garbo go to bed wondering if leaving early from a party that night would be cited years down the line as another example of her reclusiveness? The words of deities are collected and pored over. Maybe better to say as little as possible.

So, I’ve ended where I started – asking myself what it must have been like to be at the centre of this swirling dream of a created identity. To look on as a fantasy version of yourself is prodded and moulded into life, captured one flawless image after another, given a monetary value, processed into immortality. For the so-called goddess herself, it was as frustrating and anxiety-making as any high-paid job might be. Stiller and Pabst had played a major role creating the Dream Woman. But for Garbo, it wasn’t even a dream job.

When I first saw the mesmerising final screen tests that Garbo ever did, I built my own story around them. These stunning images from 1949 were for a film that would have marked her return to form after a short hiatus. I assumed that she was forced into attending and longed to escape back into her comfortable early retirement. In fact, she went willingly for the tests and hoped dearly for the film to come about. When the backers pulled out and the project was scrapped, she didn’t disappear into mysterious silence as befits a beautiful Dream Woman. She retreated, humiliated and hurt, knowing that time was against her and that her career was probably over. But she got over it. She exercised every morning to stay slim and considered the offers that came her way, rejecting them all. The rest of her life may have been film-less, but it wasn’t friendless. She travelled, smoked a lot and bought art for her New York apartment. She went into old age presumably as we all do, becoming so detached from our younger selves that they might as well be other people. Except that, of course, for Garbo and the other screen deities of her Golden era, their younger versions were other people: lit, shaped, smoothed, haggled over, paid-for and captured as exemplars of impossible perfection.

References, further reading and links.

Paris, Barry, Garbo A Biography, first published n the UK by Sidgwick & Jackson, 1995.

Hall, Sarah F, Inflation and Devaluation, Gender, Space and Economics in G.W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, from Weimar Cinema (ed. Noah Isenberg), Columbia University Press 2009

Schaller, Mark, The Psychological Consequences of Fame: Three Tests of the Self-Consciousness Hypothesis, University of Columbia. Schaller1997Fame.pdf (ubc.ca)

The Psychological Consequences of Fame, article in Psychology Today by William Todd Schulz, 2009 The Psychological Consequences of Fame | Psychology Today

Greta Garbo Screen Test (Cinematographer: Joseph Valentine, May 1949). – YouTube

Image of Greta Garbo taken in 1925 by Arnold Genthe

——————————————————————————–

7.2.2022

IT’S (STILL) A MAN’S WORLD

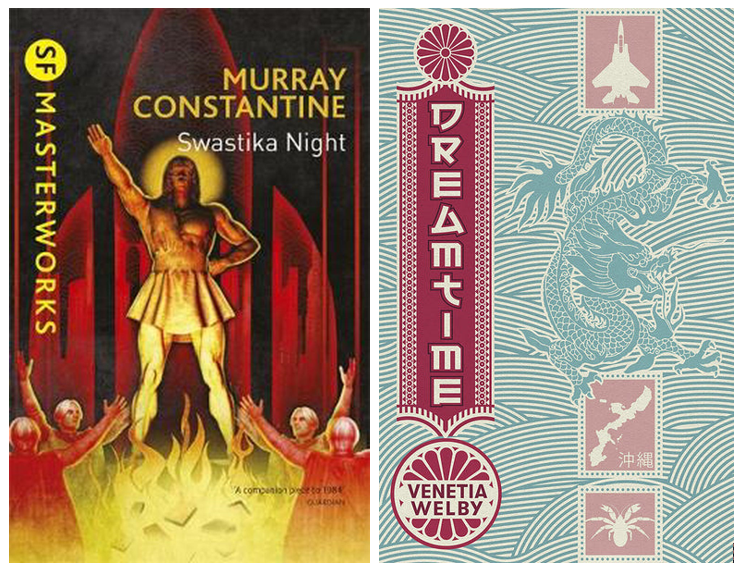

Visions of a brutalised future in Swastika Night and Dreamtime

The future, in its literary visitations, is almost always a bad place. It’s a warning, an illustration of what the end stop of an ill-fated trajectory might look like. There’s a high price to pay when you tinker with society and a would-be utopia reaches its seeming perfection darkly, by jettisoning its oldies, burning its books or amending the genes of its unborn. This future world may look familiar but it’s as distorted – and perilous – as a nightmare.

Two works of speculative fiction, written 80 years apart and with very different preoccupations, have nonetheless both reached this nightmare scenario in some strikingly similar ways. Swastika Night, written in 1937 by Katharine Burdekin (under the pseudonym of Murray Constantine), and Venetia Welby’s recently-published Dreamtime, both present us with a very masculine world order that is, either officially or from habit, extremely violent towards women. For Burdekin, this vision is at the core of her future world. For Welby, it is part of a wider evocation of the violence being committed against the environment.

Burdekin’s extraordinary novel, written only a few years after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, managed not only to foresee the war and the holocaust, but also a military alliance between Germany and Japan. On top of this feat of remarkable prescience, she created the father of all dystopias – a place where one half of the population has been dehumanized. Women are seen as animals, referred to several times in the book as cattle, in one place described at length as dogs. They are reviled by men, found physically disgusting, their heads kept shaven and dressed in shapeless rags. They are corralled together in caged compounds, where men visit them for the purposes of reproduction. Male children are taken away from their mothers at the age of one so that they can be reared properly among men and prepared for the world.

And what kind of world is it? Burdekin conjures up a real horror. After a twenty-year world war, Germany has come out triumphant alongside its ally, Japan, and half of the planet is run by Nazis. The Jewish population has been entirely wiped out and the few remaining Christians are ridiculed and held in contempt – barely above women in social status.

The book is set around 700 years since this victory, by which time genuine world history has long been replaced by a Nazi version. Germany and her subject people worship a god called Hitler, a magnificent warrior with long blond hair and rippling muscles, a giant. He is the beginning and the end of history, a superbeing who sprang from something called the “explosion”.

The future envisioned in Swastika Night is not particularly futuristic, it has to be said. If anything, the world run by the Nazis feels medieval. Technology doesn’t seem to have moved on from the 1930s and society is largely unenlightened, with limited literacy and next to no artistic culture. Apart from the Fuhrer, the most powerful figures are the Knights, venerated and untouchable, born into their priestlike roles. The book’s hero – an English aircraft engineer called Alfred who is on pilgrimage to Germany – comes face-to-face with one of these Knights, an ageing free-thinker called von Hess. A central, wide-ranging conversation between Alfred and von Hess is as much a part of the book’s action as the events either side of it. Von Hess has an artefact to show Alfred, an ancient photograph that has been kept hidden by his forefathers for centuries. It shows a group of people, one of them a short, dumpy man with a lank swathe of hair across his face and a smear of a moustache. When Alfred is told that it is in fact Hitler then his mind simply can’t take it in. What’s more, the beautiful long-haired boy standing beside Hitler in the picture is actually a woman – another impossibility! To know the truth, is to start the process of dismantling the lie. But the lie is 700 years old and ingrained.

Von Hess can see that change is coming. Women seem to be giving birth to fewer girls and the future is potentially sterile. The so-called “Reduction”, where women historically allowed themselves to be lesser humans and ended up as non-humans, remains somehow in their collective subconscious and may be affecting the birth rate. Even Alfred – a rebel, who dares to dream of an anti-German uprising – can’t quite get his head around equality and feels no affection for or attachment to the mother of his own sons back in Britain.

Von Hess explains to Alfred the roots of this inequality.

“…when the Reduction of Women started, the Christian men acquiesced to it, probably because there always had been in the heart of the religion a hatred of the beauty of women and a horror of the sexual power beautiful women with the right of choice and rejection have over men. And when women were reduced to the condition of speaking animals, they probably found it impossible to go on believing they had souls”.

Slowly, a situation that may appear preposterous to the reader, gains a foothold in the imagination. The great religions are not that great when it comes to female sexuality. It is a thing to fear and to suppress. If this level of repression has happened before, suggests Burdekin, then what’s to stop it happening again – particularly in a mindset that worships the powerful, dominant, martial male?

Burdekin plays the same unsettling hand when it comes to Alfred’s distaste for the German empire and its uncompromising control over its subject peoples. Von Hess makes a staggering revelation to Alfred. Not only did his country, Great Britain, once rule over an extensive empire but it was Germany’s jealousy of it that encouraged its own imperialism. “You ought to be ashamed of your race, Alfred, even though your empire vanished seven hundred years ago. It isn’t long enough to get rid of that taint,” says von Hess.

Alfred is groping towards an idea of what his country might once have been like. When the collective memory banks are wiped, can anything come through? The myths and folklore of a people are almost its most precious possessions, a collection of mutable yet fundamental words and images that contain the essence of nationhood. Alfred talks of the “darkness” of the unknown past of his country. “So much mistiness,” he muses.” Nothing but legends. England’s packed with legends. I expect all the subject countries are.”

Alfred knows too much to go back. While on pilgrimage, he has come across an old friend, Herrman, a slow-witted, lumbering German, who fights first, thinks later, and personifies the state of his empire: mighty but with damning points of intellectual weakness. Alfred is armed by knowledge. Hermann destroyed by it. Burdekin has given us a handful of memorable individuals for a reason. The Nazis have removed individuality as a prerequisite to totalitarian governance. Their story – in effect, their conversations – is the truly fascinating journey of this novel. Ideas blooming where there had been none. Scintillating moments marking the grasping of truth. But, she asks, is it enough?

Inequality. Imbalance. The same thing. For Alfred to set in motion any kind of resistance to the world order – to bring back the balance – he has to start by questioning his own attitude towards women. It’s not only an issue of freedom, but one of human survival. The Reduction of Women ends – hundreds of years down the line – with the ruination of all humanity, puts everyone on the brink. The brutal, misguided dream of a handful of sociopaths, wreaks untold damage and sets a collective nightmare in motion.

*

Damage is also at the heart of Dreamtime. And, just as in Swastika Night, it’s so deep-seated, so far gone, that the nightmare scenario is of its incurability. Unlike Swastika Night, however, the nightmare is not hundreds of years away, but just around the corner, in a palpably near future. Having said that, there is much that feels almost hallucinatory in the book, time-shifting, with science and folklore swimming in and out of focus, as though seismic climate events have not only shaken the planet’s surface, but disturbed its deepest myths and superstitions as well. Just as Alfred perceives that mistiness of the past in Swastika Night, so chimerical forces bubble up into the human world in Dreamtime. And exactly as Alfred’s name nods to past glories and legends, so the names of Dreamtime’s characters – Sol, Hunter, Phoenix – suggest an allegorical element to the narrative.

No one goes undamaged in the world of Dreamtime, from the emotionally-scarred heroes Sol and Kit, to the hardened American soldiers and the vulnerable Japanese islanders they have been sent to guard. The capacity to damage seems inherent. It’s set in motion, Welby suggests, by early sins, by the unleashing of nuclear arms at the end of the Second World War. Short-term political decisions are, she indicates, at the root of manifestly disastrous long-term outcomes.

Dreamtime is the name of the American cult where Sol and Kit – possibly sister and brother, possibly not, certainly would-be lovers – spent their earliest years, looking out for each other while trying to escape the cult’s charismatic, sexually-deviant leader, Phoenix. Sol – now on the cusp of thirty – has been in rehab on and off to cope with drug addiction. Wild, beautiful, impetuous – perhaps even doomed – she has become obsessed with finding her biological father. All she knows is that he was a soldier and that he may now be based in Japan. Kit, who cannot be apart from her – she is his dangerous and yet life-giving sun – is going along, albeit reluctantly.

What follows is a complex, harrowing and remarkable travelogue, from the unbearable aridity of Arizona to the toxic fragility of Japan, where American military bases are now peppered around its archipelago as a bulwark against Chinese aggression. As the search for the mysterious soldier-father intensifies, so Sol and Kit leave Tokyo behind for the islands. They are accompanied by Hunter, an irresistible, godlike Marine, muscular, all-knowing, who has taken it upon himself to act as Sol’s guide and bodyguard.

There is a restlessness in the telling of their journey, a jumpy, neurotic second-guessing. The world seems to be crumbling under their feet, a storm always ahead. The area is suffering. Its seas are poisoned, its land under constant threat from the encroaching oceans, its culture being replaced by an American way of life and its young women at risk from the “friendly” occupiers.

Welby’s depiction of ecological disaster is breath-taking but it’s also the more nuanced threats that resonate. To get to Japan, Sol and Kit take one of the last scheduled passenger flights before all planes are grounded for environmental reasons. Air travel, taken for granted for decades, simply ceases and distant parts of the world become closed off. The sky is not the only forbidden area. The seas around Japan have become so dangerous that no one dares swim in them. Seafood – once a staple of the Japanese diet – is off the menu, too risky to human health. Sol runs into the sea, heedless, refusing to believe that anything can harm her. Kit, trepidatious and always aware of the wrongness of their incursion into a world that doesn’t want them, longs for his parched Arizona home. He is cerebral, she all instinct. If she personifies the headlong rush of the world towards disaster, then he is the conscious penitent who looks on aghast and helpless. “All of nature is hostile to humans now,” he realises. “The sea, the sun, the beach, the trees.”

For Welby, there is a close relationship between male sexual violence and the remorseless plundering of nature. The long-term effects of an abusive cult leader, who preyed on doped-up mothers and their children, is still being felt by the grown-up victims. US Marines, drafted in to protect the Japanese population, are actually responsible for their harm, young local women disappearing with regularity at the hands of servicemen. And then there is Hunter, whose sexual voraciousness is draining and overpowering. Sol, looking for a father and a protector, either puts herself in perilous positions or is taken advantage of. Slowly she is being eroded away and yet there is something still powerful at her core. Her will is indomitable.

Dreamtime works towards a conclusion of enormous impact, a kind of ecological Heart of Darkness. But even in this cataclysm we recognise the familiar sense of denial. Kit, who is witness to the nightmare, who would rather not know, is not alone in struggling to grasp what is happening, even when it’s happening before his own eyes:

“Death is something people are more familiar with these days. A thousand climate migrants have died trying to make the crossing, or a thousand perished in the landslides, or ten thousand or a million dead of drought, dehydration, famine, pestilence. The constant throwing out of numbers has inured most people to the reality, and as all distant reality has been replaced by the virtual, it is easy to stay inured, even to deny completely.”

Dreamtime – in all its breathless intensity of noise and colour – is the unapologetic opposite of denial.

*

Have we lost the battle? Is coming face to face with disaster likely to pull us back from the brink of ecological disaster? Can we stand up and rise against a brutal political regime? Is it for a dystopian novel to even attempt to answer that question? Maybe its job – as demonstrated by these two visionary books – is to throw us into the nightmare and let us reside in a worst-case future for a while. Just to see how it feels.

Swastika Night by Katharine Burdekin, writing as Murray Constantine, is published by Gollancz as part of its SF Masterworks series. It originally came out in 1937.

Dreamtime by Venetia Welby was published by Salt in 2021.